Vocational education, a mainstay of the American school system since the early 1900s, has experienced a slow but steady decline in the last few decades. What was once a pipeline into stable, middle class employment has become, in many schools, a shell of its former self; programs have either been slashed in the wake of “accountability” and college readiness mandates, or have become options of last resort for students who don’t do well in college-track programs.

The Smith-Hughes Act provided federal funding for vocational education for the first time in 1917. At the time, the nature of schooling and work in the United States was changing dramatically. With rapid industrialization underway, it was no longer safe or feasible for kids to learn a trade at their parents’ sides, and apprenticeships, which had once taken place in small, specialized shops, were no longer practical as a way of training new workers at a rate adequate to meet production demands. The country was rapidly becoming more urbanized, which meant that fewer children were following their parents into farming. At the same time, waves of immigrants were flooding urban centers. More and more children who weren’t headed for a college education were staying in school beyond the eighth grade. Schools had to find something for all of them to do; vocational education was intended to provide the answer.

At first, these programs meshed perfectly with the demands of the economy. Vocational programs partnered with industry leaders to ensure that students were learning the skills that were most needed in the job market, and in turn, local industry provided high schools with up to date equipment to use in their training programs. Graduates were all but guaranteed that their skills would be marketable, and that they could count on making a good living until retirement. There were many good union jobs available, and the market could sustain individuals in a trade for their entire careers. As late as the early 1970s, only one in four middle class workers had any education beyond high school.

Around this time, though, the seeds were planted for erosion in the quality and success of job training programs. Concerns about equity had led many programs to expand in order to accept more students, making it more difficult for local factories to continue providing materials and equipment for training. Eventually, the partnership between industry and vocational education programs all but disappeared.

Toward the end of the 20th century, the demands of the job market shifted; increasing globalization and rapid advancements in technology dictated that workers needed to be ready to learn new skills and transition to different jobs, perhaps multiple times over the courses of their careers. It was no longer possible for workers to rely on the fact that they could spend their entire working lives in one trade.

As these changes were taking shape, education was faced with a movement toward higher standards and increased demands for “accountability.” One major consequence of these changes was pressure to provide every student with an education that would make him or her “college ready.” Many job-training programs were eliminated in the wake of these demands.

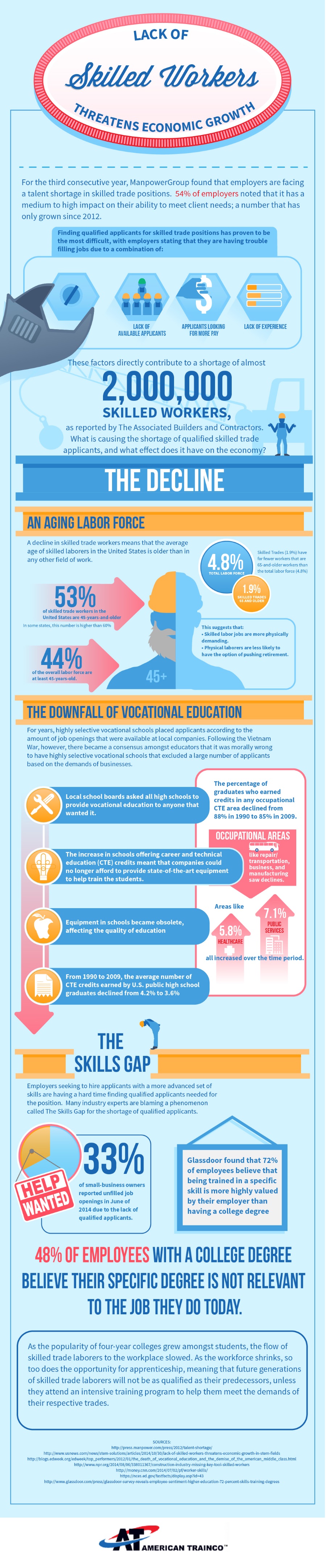

The future of vocational education remains uncertain, but one thing is clear: the unfulfilled need for qualified, skilled trade workers is a threat to the nation’s economy. The infographic below presents more information on the current state of job training in the United States.

Source URL: https://www.americantrainco.com/infographic/skilled-worker-infographic.aspx

Leave a Reply